tv [untitled] September 27, 2010 11:30pm-12:00am PST

12:30 am

defender's office. first in los angeles in 1916 and then here in san francisco in 1921. so, remember, you have to keep trying. go after your dreams. i did. wait if you must, but in the end, you will win. [applause] >> thank you very much, and shaffs sharon avey. thank you, sharon for the incredible presentation. i also want to mention she has written a book about clara fultz. if you're interested, get a copy of sharon's book and get it on amazon or get it here in the lobby.

12:31 am

12:32 am

small ones and how they affect not only the way in which the criminal justice system either works or doesn't work but also how it affects the lives of every day people. our first panelist is amy bach. miss bach spent eight years studying courts throughout the country and she wrote a book called "ordinary injustice." it is really an incredible book that looks at the perspective of the justice system from a contract public defender's per spivet, a prosecutor's perspective and a judge's perspective and she was able to come up with some brilliant insights about not whoonl the problems are not only what the problems are but what to do about it.

12:33 am

professor bener wrote incredible tweetice studying public office throughout the state of -- tweetice studying public office throughout the states of california. why they are not equipped to properly handle all of the cases that they have and the challenges involved in it and what to do about it. next we have the public defender of fresno county. ken tagucci. he has fought a valiant battle. it is still going on on. a raging battle with the board of supervisors in fresno county and last year, they cut his staff by 12 attorneys and at the same time he was expected to handle more cases. and the county responded when

12:34 am

public defender said he could not do any more cases by trying to outsource the responsibility of the public defender to low-cost bidders. next we have john truzano who comes from washington, d.c. he is the co-founder of the justice project and john recently co-authored a report about accountability of both prosecutors and judges and so he studied why misconduct curse and what steps need to be taken to ensure that it doesn't happen and finally we have sean levy. he did a serious about the fact in santa clara county they were

12:35 am

not providing lawyers at the first appearance in misdemeanor cases. he will tell you about his series of stories that actually changed the practice in santa clara. i want to start with amy and if you can tell us what is "ordinary injustice" and how does it manifest itself? >> ordinary injustice happens in a courtroom where there are smart, committed, hard-working people, professionals. but they are routinely acting in ways that fall short. what it is that people and their positions are supposed to be doing. and they don't even realize that anything is missing or that their behavior has devastating consequences for regular people's lives. so this is really the meaning of

12:36 am

ordinary injustice that mistakes become routine and the legal professionals can no longer see their role in them. >> can you give us some examples of what you found in your eight-year saga of studying the court system? >> sure. the best way to perhaps get into it is to tell you how i first came across it. i had just graduated law school from stanford and i had clerked for a federal appellate judge in miami and the jurisdiction was florida, alabama and georgia and i wrote a story after my clerkship for the "nation" magazine and it was picked up everywhere. they said if you can do this again, we'll give you a year to write about civil rights which sounded pretty good because i wouldn't have to make major decisions about my career and i could write stories about things

12:37 am

that interested me and i began to sit in courtrooms all over the country. the court that made me realize that i wanted to write a book was in green county, georgia. it was a beautiful place. president bush vacationed there three times during his presidency. i walked up the stairs and i saw the public defender there and he is a man named robert who sa major character in chapter one and he has tons of people swarming around him and they are waving papers trying to get about two minutes with him before their cases are going to be called before the judge. now this is the way it worked here in green county. he would call their anytime. john smith, are you here? and then john smith would come and be told what the prosecutor was offering and people had called and not heard back.

12:38 am

they didn't get any attention to the individual circumstances of their cases. instead, they were called before the judge and another attorney who even left about the case would stand there almost like a piece of cardboard and the people would plead guilty. now it was incredibly obvious in court that day that people had no idea what was happening to them. people started to cry in the middle of pleading guilty. wait, i'm pleading guilty. i didn't realize i had agreed to go to jail. it was really a mess mess . what i really learned later is that robert was a croobt defender and he had a -- contract defender and he had a full private practice representing people who paid him money and he had earned a sum of money from the county and had to represent as many people as the prosecutor was going to charge and during the two-year period, he had represented twice the

12:39 am

number of people that the american bar association recommended as the slutes maximum. now -- absolute maximum. now, there was something else that happened that day in court and this is extremely important. i was sitting there and there were these long, dark, wooden benches and everybody was sort of creeking because the judge, the prosecutor and the defense attorney were all huddled together at the front. now, all you could really hear in court was the creeking to have wooden benches. you couldn't hear anything that was going on and i was trying to take notes for my story and next to me was this guy. his name is steve bright. he is head of the southern center for human rights in atlanta. he had come because i told him imi was doing this story and he had been suing different counties across the state saying they were providing a lack of quality indigent defense. he said i'll come sit with you.

12:40 am

he state your name turns to me and said amy, you're trying to take notes for your story. you can't hear anything. why don't you ask the judge to speak up. i said i'm not going to that. i'm here as a neutral reporter. i'm a journalist. i'm not going to make myself -- i don't want to raise a instructous. the whole thing is kind of pointless. all of a sudden steve, who has this deep, booming voice raises himself halfway up and says your honor, if you wouldn't mind please speak up. we can't hear. thank you very much. the whole place like turns and looks at steve and we're sitting in there and as rust as commotion as it was before, you you can't hear a pin drop. the judge says who are you?

12:41 am

come before me. i want to know what you want and steve goes like this. your honor, we can't hear you. if you wouldn't mind, speaking up. the judge calms him to come before him and steve crawls over everybody's legs and gets before the judge and he takes over the courtroom. he says your honor. we're all here. we're missing work. we have left our children in the care of others. this is a public hearing and we would like to hear so if you wouldn't mind please speak up. everyone starts to cheer. that's right. this is a public hearing. i want to hear. people are clapping and the judge is pounding on the gavel. the judge says all right. all right. there is a lot of interest here. we're going to take 15-minute break and we're going to come back and i'll figure out what to

12:42 am

do. 15 minutes later, by the way in the break everybody is coming up to steve and they are like, you know, shaking his hand and begging him to represent them. so, so, so she comes back and puts up on a microphone and for the rest of the day everybody could hear but i went back to that court the next day and steve was gone and so was the microphone. i went back to the court for weeks on end for the next five years because i wrote a whole chapter about this community and there was never another microphone and there was always that huddle. that huddle is what my book is about. it is about people who work in the system who become more attached to each other than they are to the jobs that they are supposed to be doing. and what they do is they lose a sense of what it is that is important and who it is that they are supposed to be protecting and instead, the justice system becomes more about them and this really

12:43 am

became the seed for ordinary injustice in the book. [applause] >> that's quite a story. remember, when we go to court tomorrow, ask the judge to speak up. >> i've been reminded by doctors. they have to wear a -- a sign on their shirts that say ask me did i wash my hands. can you imagine if a judge had a sign ask in to speak up. >> or ask me if i'm being fair. [laughter] so, you know, the things a you witnessed, amy, i'm going to ask professor bener to talk about what is the culprit here? are we talking about incompetent

12:44 am

lawyers? lawyers who don't care? are we talking about a system that is set up for lawyers to fail? what were the findings that you made as a result of looking at public defender offices throughout california? >> i'm going to speak more to structural aspects of it. i think amy is speaking more of the cultural and human aspects of the job. our system as you know is based on the theory that any accused person who comes to court is presumed innocent. they are protected by that preassumption. that's why, in fact, we provide council for an indigent person whoke not afford counsel. unfortunately, it paints a rather discouraging picture because i found that there is a fundamental disconnect between that theory and actual practice in california and that

12:45 am

disconnect occurs because the system, the indigent defense system is funded by local politicians. now these are public officials who must make decisions. they must choose among many worthy, competing concerns that are vying for those scarce taxpayer dollars and not surprising, most of them or at least many of them assume most defendants are guilty, they tend to make decisions about indigent defense systems based on the presumption of guilt. that has made a system in many county where is processing the presumed guilty as cheaply as possible is given a much higher authority than investigating the possibility of a defendant's innocence. we have seen budget cuts while caseloads have continued to

12:46 am

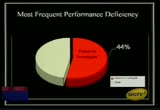

increase and in an increasing number of counties we have seen the fate of the indigent accused being put up for bid by offering contracts for attorneys who'll do that work the cheapest. that has a profound effect on our criminal justice system because the vast majority of criminal defendants are indigent. they are not able to afford their own private attorney. we found for example, more than eight out of 10 felony defendants were indigent and must therefore be provided with counsel. we did a study of cases looking at the systems and we discovered that the system for providing the sturl providing indigent defense services in many countieses is filing perform the most basic duty required of a defense attorney and that is to conduct a thorough investigation of the facts. that is what protects the

12:47 am

innocent from wrongful conviction. i think i have a graphic here that shows what we found in this study of over 2,000 cases, almost half of the convictions that were overturned on appeal because of defense attorneys involve the failure to investigate. now you might think that this is a problem with the lawyers. unfortunately, we tend to blame the problems of our system on the individuals involved and that ignores the wider systemic factors. i think failure to investigate is a good example of that. why we had this failure to investigate results not from individual lawyers so much as the inability of individual lawyers to do that job because they don't have the resource. over 2/3 of the judges that we interviewed admitted that they had a problem in their county investigating indigent cases because they didn't have the

12:48 am

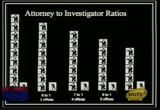

resources. all of the public defenders that we interviewed and sent questionnaires to that we surveyed all of them reported they had not have enough adequate investigators on their staff and in fact, a number of these crabblingt defenders don't have any -- contract defenders don't have any staff investigatedors at all. the national standard promulgated by goals states there should be one investigator for every three attorneys. we found that most offices in this state don't comply with that. they don't meets that requirement. some had as many as nine attorneys to one investigator. that problem is coming pounded by the fact that attorneys also are overloaded. more than three out of four public defender offices reported excessive attorney caseloads were a significant problem in their office. you have a multiplirefect.

12:49 am

if there are mot enough hours in the day to investigate the cases obviously some soft cases don't get investigated. that's the problem that we're seeing. now other problem of course deals with well, why is that situation? public defenders represent the lion's share of all of the cases. yet what we see, you would expect them to have rough parity with the prosecutor's office. we don't see that. what we see statewide is for every dollar spent on prosecution only 53 cents is spent on average for the indigent accused. yet in some counties as much as 95% of all the cases involve indigent defendants. continuing to underfund indigent defense and continuing to tolerate excessive investigator caseloads and excessive attorney

12:50 am

caseloads, if we continue to do that we substantially impair the ability to provide good reputation. >> thank you very much. wow. 53 cents to a dollar. [applause] that's why i'm always broke. all right. let's go to public defender kenneth. ken, tell us. you are in fresno. first of all, what is it like in fresno? [laughter] and tell us about this battle that you have been going through where, you know, it almost sounds like a horror movie where they are going after you with a buzz saw and at the same time, they have used contract attorneys to try to undercut the work that your office does. >> well, the problem in fresno, it is hot. trezz know is hot of course in

12:51 am

the -- fresno is hot of course in summertime. it is hot all the time for me. i think the problem just mentioned right now is disparity in the funding theme as opposed to the ore parties involved in the criminal -- other parties involved in the criminal justice system. most of the funding agencies for us is almost 100% from the county. while the prosecution has the benefit of grants. in fact, i believe the district attorney might have at least half of their budget is provided by grants. that is not provided to the indigent defense providers. federal grants are almost all directed toward prosecution and law enforcement. so the problem to have vast resources that i'm facing right now is that you have grant funding the police department,

12:52 am

the sheriff's deft, the district attorney's office. there is a share that -- etc., etc. that share, which for them is a portion of their funding is almost my entire funding so when you say you're going to cut 13% off everybody equally. well, 13% for us is more than 13% of their entire budget than for the other agencies. now the problem is that's the ripple effect we just had here. now they still have their investigators because they have other agencies that provide the investigation. we don't. our investigators are the ones that have to be trimmed off because we can't pay for them. our attorneys, again, they are paid for by the county. we have to cut back our attorneys. meanwhile, the prosecution, yes, they may have to cut back the attorneys. there are a lot of attorneys still being funded by these grant positions.

12:53 am

so we're up against a resource that doesn't go down in the same proportional rate as we do. we get contracted further than they are. that's the disparity now. they try find a way to make it cheaper. those ideas are always popping up. you see them all over the state. is it cheaper to do it by privatizing the public defender? as opposed to maintaining the institutional public defender? i think that we see what we see as public defenders, maybe i'm biased in this regard but we have only one focus in mind and that's to our clients. our clients come first. damn to or the peete pidto if it is going -- damn the torpedo if it is going to cost us money. they have a conflict of interest. they are for the profit margin. and now profit margins might override to going forward and doing what it takes to get the

12:54 am

job done and i think that is the difference in attitude a lot of times i'm seing in the providers you from the institutional public defenders opposed to contract public defenders. >> great. thank you. [applause] thanks very much for coming up here and being part of this discussion because we want to be able to support you in the work that you're doing. i'm going to go back to aimy before going to john and one of the things that you talked about in your book, is the role of prosecutors. and the role that prosecutors play in justice. prosecutors as we know have a tremendous amount of power. they have the ability to decide who to charge or when not to charge. what were some of the things that you noticed or found about prosecutor offices in your book and then i'm going ask john to talk about what his study shows in terms of what prosecutors are

12:55 am

doing right and what they are doing wrong. >> well, prosecutors pretty much have unfair discretion to decide what to prosecute and whatnot to prosecute. and i had gone to a county in mississippi and i got there because there had been a front page story staying county was suing the state saying it didn't have enough money to defend the poor. so i get to court and i'm expecting to see lines of people coming out the door like i did in georgia but when i get there there were only eight people. and was sort of perplexed. where was everybody? was thereto not a lot of crime in this place? i start giving out my cards

12:56 am

trying to learn about this place. my cell phone starts ringing off the hook. everybody has got a story. at the library, the librarian leans across the desk and says my home was broken into three different types in one week. they came and they interviewed me. they said they knew who the guy was but the case never went anywhere. so i had all of these stories and went to the clerk to have court and she is a woman named miss wiggs. she has a helmet of white hair and bright blue eyes and a plain talking way of speaking. i said what is going on here and she said you want to know what's going on? i'll tell you. she points to this list above her besk and now these are lists, names of defendants who have been changed with a crime in lower court in the justice court and they have been bound over to the circuit court for the prosecutor to bring to grand

12:57 am

jury. by law in mississippi, the prosecutor has to give every case to the grand jury and the prosecutor can say there is not a lot of evidence in this case and this case has resolved itself, i don't think you should indict but it is people who have to decide what gets to court and what doesn't get to court. she said here i have 80 people on this list and when we came to court on the other day there was almost nobody there. people call me all the time and tell me horrible things that have happened to them and their children. their kids were molested. they were beaten up. someone was arrested yet the crime never goes anywhere. i asked her if i could use the list as a road map to see what was going on in the county. so i copied it and started going through and getting all the case files and what i found was that when there was a big, important case like there was a big murder and some people from outside the county came in and murdered an

12:58 am

entire family and lit the house on fire, then the d.a. would go full hog and would prosecute the case to the nth degree. but when cases affected regular people, even a carjacking or many other crimes that i talk about in the book, those cases got put asise side because his investigator would say i don't know if we can win this one. and that one woman, she had been beaten up by her boyfriend underneath a bridge. her daughter and her niece were inside of a locked car watching, screaming to get out and they watched as he pummeled her with a tire iron and at the scene of the crime according to the police report there was a hair we've, there was one of her shoes and this was a picture in the back of her file that showed

12:59 am

these huge bloody contusions on her face, a stripe. she was in the hospital for three days and she couldn't work anymore because he had beaten her so badly on her back that she couldn't bend over. she was a housekeeper in a casino. i tried to figure out why wasn't this case prosecute. i talked to the victim and the perpetrator's family and i talked to the police officer and i talked to the investigator and i couldn't fitting out. why? why? why? what is wrong with that case? why didn't this case go anywhere? i went to miss wiggs. i said why didn't this case go anywhere? she said let me look back and see when was the last time a domestic violence case was prosecuted? it turns out this prosecutor hasn't prosecuted a domestic violence case in

69 Views

IN COLLECTIONS

SFGTV2: San Francisco Government Television Television Archive

Television Archive  Television Archive News Search Service

Television Archive News Search Service

Uploaded by TV Archive on

Live Music Archive

Live Music Archive Librivox Free Audio

Librivox Free Audio Metropolitan Museum

Metropolitan Museum Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of Art Internet Arcade

Internet Arcade Console Living Room

Console Living Room Books to Borrow

Books to Borrow Open Library

Open Library TV News

TV News Understanding 9/11

Understanding 9/11